Swami Vivekananda and Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Two saints who brought Indian spiritualism to the global stage in their own different ways had millions of followers and several high-profile disciples and caught the imagination of people distressed by the march of crass materialism and looking for inner peace. Incidentally, they also share the same birth anniversary — on January 12. If the Maharishi developed the concept of Transcendental Meditation (TM) which caught the fancy of the likes of the Beatles, the Swami seized the imagination of the world community with his famous 1893 speech at the Parliament of World Religions. One media commentator remarked that the Swami was an “orator by divine right”. Yet another, after the stirring speech in which the Swami put forth his views on Hinduism, noted “how foolish it is to send missionaries to this learned nation” (India, which boasted of such a spiritual stalwart).

The Swami and the Maharishi worked almost a century apart, but what they did can be consolidated in favour of India’s status as a spiritual power. Both saints had strong opinions and were way ahead of their time, and this country, as well as the world, is now even better able to appreciate the contributions of these giants. They have long departed but their teachings are quoted to this day and there are thousands of those who strive to imbibe even a fraction of the thoughts of those great minds.

Swami Vivekananda’s life and work have been well recorded and evoked innumerable times. By addressing his audience at the Parliament of World Religions as “sisters and brothers of America” (for the US was the host of the event), the Swami made an instant connect that helped him effectively propound the essence of Hinduism and dispel apprehensions about the faith. His rise as among the world’s foremost voices in spiritualism was not sudden. He was inclined to meditate from an early age, in front of the images of deities such as Shiva and Ram. And, although he came from a fairly prosperous family, his mind always wandered towards the spiritual realm. The early influences of Brahmo Samaj played an important role in shaping his spiritual profile in the initial years.

However, it was after he came in contact with the spiritual leader Ramakrishna ‘Paramhamsa’ sometime in 1881 that his true grooming began. A few years after, Swami Vivekananda (then Narendranath Datta), lost his father, was feeling rudderless, and his family had slipped into deep financial problems. The first meeting, which was followed by many others, was the beginning of what became a unique guru-disciple relationship. After his teacher’s death in 1886, the young student decided to pursue the path the great teacher had shown him, took monastic vows and came to be known as Swami Vivekananda. He travelled extensively through the length and breadth of the country, meeting people, spreading the message of spiritualism — and himself evolving into a spiritual leader, of the kind which the country had rarely seen. His concept of Hinduism was all-inclusive, and he had followers from all faiths and walks of life. Soon, he ventured into the West and realised to his dismay that the likes of him without ‘credentials’ or sponsorships from noted people or organisations were not entertained. He got a break when a Harvard University professor invited him to speak there. The Parliament of Religions event followed thereafter.

Swami Vivekananda’s spiritual and religious quest also questioned many set notions of the time, which he demolished not by reactionary utterances but by simply turning to the sacred texts and explaining their true import. Indeed, much of what is being celebrated today as a natural right in democracy had been professed by the Swami in the 19th century. Let’s take one issue which has gripped national attention for now: Gender justice. Muslim women have become assertive against injustices such as instant triple divorce, lack of maintenance to divorcees, polygamy among males, unfair inheritance right etc. Women from other communities too have been waging battles against gender discrimination in matters of entry to temples and leading prayers in churches etc.

Swami Vivekananda had forcefully, and repeatedly, said that there could be no progress, material or otherwise if women continued to face bias and are ill-treated. Perhaps reflective of his agony at seeing the poor treatment of women in Indian society is this remark of his: “There is no hope of rise for that family or country where there is no estimation of women, where they live in sadness.” Although he did observe that “woman has suffered for aeons, and that has given her infinite patience and infinite perseverance”, he found no merit in such ‘sacrifices’. Instead, he said, “The idea of perfect womanhood is perfect independence”.

Such perfect independence is still a chimera, but at least there is a greater sense of awareness of what the Swami had observed decades ago. There is now a rising demand in the country for a law that would reserve 33 percent of seats in Parliament and State legislatures for women. A Bill to meet that end has been pending approval for years now, and perhaps now is the right time to push for the legislation.

We are witness to fiery debates on television channels among clerics on what women should and should not do. These religious leaders, to whatever faiths they belong, often speak in one voice when it comes to excluding women from the due they deserve as per the Constitution and as people who have equal rights. Speaking for Hinduism, Swami Vivekananda challenged those who claimed that its sacred texts had placed restrictions on women. He once demanded to know: “In what scriptures do you find statements that women are not competent for knowledge and devotion?” He said the Vedas and the Upanishads had instances of women taking the place of rishis “through their skill in discussing about Brahman”. He added, “It is very difficult to understand why in this country (India), so much difference is made between men and women, whereas the Vedanta declared that ‘one’ and the same conscious ‘self’ is present in all beings. You always criticise the women, but say what have you done for their uplift?” Now, these are words that would make clerics of all religions squirm in discomfort even today.

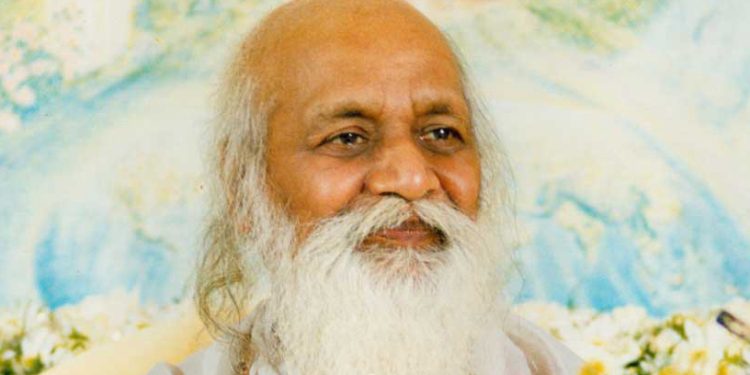

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, on the other hand, adopted a different spiritual direction, devoting himself to the construction of meditation techniques. He was more of what is termed today as the ‘modern spiritual guru’, primarily concerned with perfecting and then branding Transcendental Meditation. Nonetheless, his contribution to the Indian spiritual thought is profound. He sought to project TM as a means of achieving world peace. That this concept should have struck a chord across the world, especially the West should not be surprising. The West has always been a fertile ground and usually receptive to Indian spiritualism. Besides, that was a time when the US-Soviet Union conflict often threatened to take on military colours and drag in the rest of the world into what was being apprehended as a third World War. Mahesh Yogi’s message of peace, of meditation — to supplement mediation, as it were — found instant resonance in such a scenario. Of course, his association with the Beatles helped him gain international fame. The fallout, though, affected some of his global following, though in years thereafter some of that bitterness was diluted and a sort of rapprochement between members of the music group and the Maharishi happened.

But the Beatles episode, important as it may be to the chattering class, was hardly the crux of Mahesh Yogi’s spiritual journey. What is important to note is his legacy. The TM movement is today a worldwide phenomenon, and Indian spiritual thought has, through it, flourished over the decades. There is a Maharishi Vedic City in Iowa in the United States, besides other centres elsewhere that promote the spiritual guru’s teaching and promote Indian spiritual philosophy.

The Maharishi had set out on his exalted path with three aims in mind: Revive the spiritual tradition in India, popularise meditation among the masses, and educate that Vedanta was compatible with and not an adversary of science. The overarching desire through these goals was the spread of happiness. He said in 1967, “Being happy is of the utmost importance. Success in anything is through happiness. Under all circumstances, be happy. Just think of any negativity that comes at you as a raindrop falling into the ocean of your bliss.”

Look at it in any way, both Swami Vivekananda and Maharishi Mahesh Yogi were saying essentially the same thing, though through different words and in varying expressions: Do good, be just, remain happy.

Discussion about this post