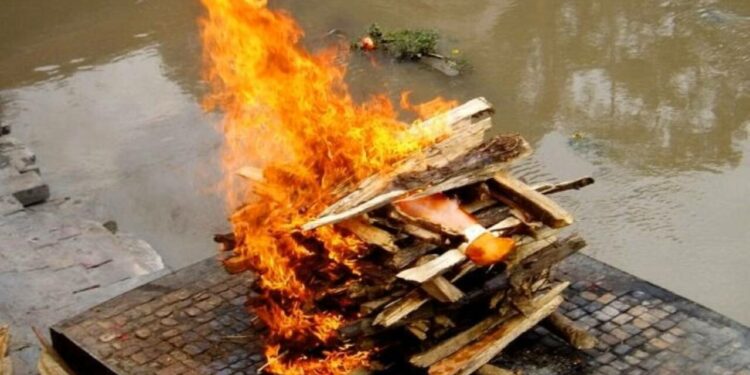

A reed-thin and drunk guy is giving loud instructions on how to arrange the wood, what to do when the arrangement is complete. Half-a-dozen men are following him quietly, carrying the wood briskly from a heap four feet away. In three minutes flat, the pyre is ready. There are enough gaps between the ground and the scaffold for the fire to move freely all along the six-by-three feet space.

A 73-year-old man, who had gone cold in the afternoon on a cloudy and humid day last Friday, is placed on it at 7.32 in the evening, 12 minutes after the sun had set and a while before moonrise. There is a just one ring around it that would get filled over the subsequent 24 hours, and the moon would be a full and lovely plate of white light.

Other than the pandit and his drunk assistant, the brother and daughter of the deceased are right next to the pyre, for they would be giving mukhagni/lighting the fire. It is the daughter who is told to pour a whole can of desi ghee over the body. The pandit tells her to repeat a shlok from Srimad Bhagwat Geeta about the immortality of the soul before she lights the fire with a loosely-knit broom of thin, long and cracking dry twigs.

Her god-sister and I are around, standing on ground that has been heated by an almost fully-burnt body behind us. There are only five grooves in the small, cemented and elevated cremation ground, two of which had accommodated people earlier that day. Some mantras are chanted and there are other rituals directed by the pandit.

After the fire is lit, we come down the steps, sit on benches in the tree lined, open ground and watch the dance of fire. For a humid day, the fire is too good. Must be to do with the generous amount of ghee that has been poured all over the body, most of all on the head and face.

(As the ghee got into the nostrils of the man, the daughter had a split second thought of wiping it away before it hit her that it was no longer her father, but just a structure or katth she was working on— as she later put it.)

The air is somewhat stunned. We hear quite a few explosions as the fire burns on. That is the bursting of coconuts kept on the pyre. Half-an-hour later, the daughter and some of us are called to throw uplas or cow dung cakes into the fire. The burning heat is too forbidding to go close. Everyone shoots the uplas from a safe distance.

A little while later, the pandit’s apprentice speaks in his loud voice, as though giving instruction to an invisible entity across the fire. As he walks away, he asks his senior if the mantras he chanted were right. It did not sound anywhere near a chant to me, but the pandit has the last word: “They were right or the show won’t be going on like it is.”

Indeed, the casual and light-hearted mannerisms of the duo, with the stout pandit even laughing to reveal his white teeth through a whiter moustache, and the apprentice reminding me of a wise tramp straight out of Maxim Gorky’s ‘The Lower Depths’, the funeral does look like a show.

The young man works at the cremation ground. He is much busier than the freelance pandit, and keeps count of the bodies he has handled per day by the number of baths he takes. Minimum five times, a bath for each, he says lightly to the man who organised the funeral.

After a bath under the tap close to the entrance of the cremation ground, the assistant spanks his hair, puts on his clothes and gets busy with his remaining task. He holds a long bamboo stick, strikes it to the ground a few times to split open the top, fixes a coconut in the gap, holds it close to the skull of the burning body, and knocks the skull in order to break it, as part of an important death ritual in Hindu religion. His job is over as is his day. There are no funerals at night.

The family stands together and visitors stream past with folded hands. As I look at the red hot fire one last time, a young woman’s words through a choked voice (earlier in the evening), ring in my ears: “This is the truth of life.” Is it? I ask myself. The answer I get is a resounding “No”.

The truth of life is how we live it. The man whose funeral I was part of, lived a beautiful life. Gentle and generous to the core with family, friends and even unknown people, he was a nursing superintendent at a government hospital in Rajasthan. He used that position to help hundreds of patients coming to the hospital. He had also mastered his knowledge of pharmacy far beyond a short course he had done, and could be counted upon to advise the right medicine for a host of problems, quite like a doctor.

A pious man, he would have immersed himself in bhakti post-retirement (although some private hospitals were waiting to grab him) but for the fact that he was struck by petuitary adenoma, a non-cancerous tumour in the pituitary gland. The man had to undergo three surgeries in four years until the doctors decided on not touching the brain again. That was in 2013.

In the following years, despite his serious condition, he fed a cow during his morning walks and buried himself in his pooja room, full of the images of gods and goddesses. He did not touch food or medicine until after he had done the pooja for hours, ignoring his wife’s protests. Over the last three years until his death on July 19, 2024, he developed multiple problems, including Parkinson’s disease on top of a three-decade-old diabetes and the pituitary gland problem.

His determined family of wife and daughter took solid care of him all by themselves (no relative, near or far, ever helped) with repeated visits to the best doctors, regular and heavy medication, proper feed, physiotherapy, and saw to it that he did not get reduced to a bed patient till the end.

The caretaker played brain vita with him and the daughter did chants with and around him, many times on phone. The mother and daughter had to forget all about themselves for three years and were on the verge of collapsing many times. They stabilised themselves with quick fixes and dug on, knowing they were all he had.

Even during the worst of times, when asked how he was, the man’s reply was, “I am quite fine.” That was a line literally printed on his mind, quite like “Shyam mila de” If he heard anyone say, “Radhe Radhe.” He had chanted Hanuman Chalisa with much fervour all his life.

During the last two years, with Parkinson’s toll on his brain and speech, he had to be prompted to be able to do the chalisa. Eight months ago, an ayurvedic doctor advised the family not to “put him through the torture of any further investigation”. Two years before that, his neurosurgeon, seeing no possibility of a revival, had told the family to “just take good care of him at home”, a euphemism for the helplessness of medical science in his case.

Feeding him during the last couple of months was an ordeal. That chewing food is a very serious exercise, involving a hundred things in the body and brain messaging system, is known only to those attending on a brain patient.

A day before the death, he ate very little. At night his breath became hard. By the morning he seemed to have improved. He surprisingly recited the full Hanuman Chalisa on his own and was heard saying “Jai Prabhu” in a clear voice twice over when he woke up. The wife could hardly believe her ears. When she asked him to recite it again, he did not do it.

After that, in between being fed a mashed apple and milk, and a change of clothes, he breathed hard off and on. But other than the chalisa he did on his own and the salutations to “prabhu”, the man did not utter a single word that morning.

As the morning passed into noon he started breathing noisily. The hoarse breath sounded rather strange, even scary, to his wife. He was lying with his hands on his chest. At one point the hands fell one after the other on the sides. The family knew it was serious. They checked his pulse and quickly strapped the blood pressure machine to his arm. It did not move from zero. The pulse was missing. Shortly afterwards a medical person came and confirmed the man was no more.

Only his close people, and those who know the power and glory of God, know the grand exit the man had—with God’s name as his last words. Talk of the last hour/thoughts/ words that decide the next life or realm. Sometimes even great tapasvis are denied the blessing of saying the holy name in the end. But this simple man seems to have won a platinum ticket for himself in the world of light.

That is the truth of his life, not the lifeless form we saw burning on the pyre. Some funerals are so light. They even shed new light on life and death.

Discussion about this post